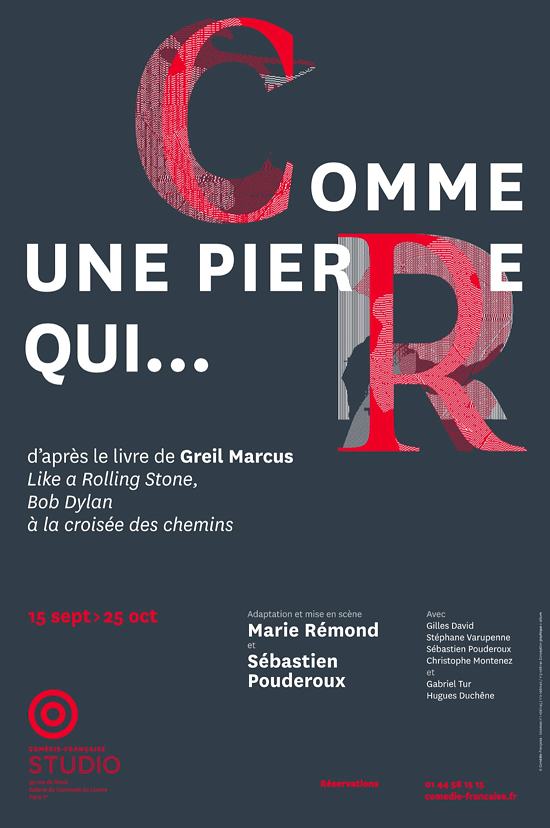

Notes on “Comme une pierre qui . . .” , Studio Théâtre de la Comédie Française, Carrousel de Louvre, 15 September-25 October 2015, Written and directed by Marie Rémond and Sebastien Pouderoux, From an idea by Marie Rémond, Adapted from Greil Marcus, Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads (PublicAffairs, 2005, Galaade, 2005)

10 October 18.30 hr

When I first spoke to Marie Rémond in May 2015 about her idea of adapting my Like a Rolling Stone book as a play, I told her to use the book as raw material. Don’t be bound by the text, or what I say happened—make stuff up. Be daring. Go as far as your imagination and the song will take you. She did that in spades.

The play opens with a very nervous young guy pacing around in front of the stage, then sitting in a chair at the corner, finally beginning to talk. It’s Al Kooper (Christophe Montenez), saying that the night before he was lying in his bed, thinking about how the producer Tom Wilson had invited him to watch a Bob Dylan session, about what a giant Dylan is to him, saying, Al, are you really going to go to this and just watch? Come on, Al, you’ve got to take a chance, are you really NOT going to try and play on this session? I may not be the greatest guitar player in the world, but I know how to play guitar.

I thought, this guy is good. He was convincing, subtle, and engaging: you were brought right into his dilemma. And that would be the company: every actor would be right as an actor, creating his own aura and space, creating and inhabiting a character, finding his rhythm, and also able to truly play his instrument, on his own and as part of a group. (I asked later why two white actors were playing two black characters, Paul Griffin and Tom Wilson—a friend said, if that, why not a woman playing one of the characters?—and was told there were almost no black actors in the company—in France, odd, but that’s what the program gallery says—let alone those who could play, and the one person they tried to get was committed).

The Kooper character climbs up into the set, Columbia Records Studio A, which is all instruments and mike stands. He’s carrying his guitar in a bag, sits on a chair, pulls out his guitar, puts on shades, affects the air of someone who belongs there, begins to play. Bobby Gregg (Gabriel Tur), a handsome, downcast guy in a light beard, sits down behind the drums, and then Paul Griffin (Hughes Duchêne), a somewhat goofy-looking character who looks about 18, trying out the piano and organ, and finally Mike Bloomfield (Stéphane Varupenne), blond, straight hair, some

what beefier than the others, an immediate physical center of gravity, coming in wet from the rain, guitar without a case, wipes it off with a towel, dries his hair, fingers a few notes—and it’s instantly, plainly real that Kooper would pack up his guitar and get out of there, realizing he could never play with this guy. Varupenne communicates this with his fingers, but also his body, and his face, the command he has of himself, of his guitar, and of the session.

Sébastien Pouderoux, with Rémond the co-writer and director, comes on as Dylan, in black and a black and white polka dot shirt, with an acoustic guitar. He answers questions with a curt note on his harmonica.

At some point, everyone will sit or stand at the front of the stage to address the audience, in the mode of talking to himself, starting with “Yesterday I was lying in bed.” Bloomfield talks about going over the song with Dylan and Dylan telling him to run the session, tell the musicians what to do, he doesn’t want to talk to them, and hilariously about how what it really is, all it really is, is “La Bamba,” they’re doing a remake of “La Bamba”: “Essentially, it’s ‘La Bamba.’” Gregg is afraid his wife is about to leave him (with a phone call in the middle of the session, she does). Griffin says he’s “the lumpenproletariat of Columbia,” treated with less than disrespect, displaced by never-played-organ Al Kooper, who becomes the star of the session, Griffin shoved behind the piano, where Dylan complains about his time. Near the end Tom Wilson (Graves David) appears—we’ve heard his disembodied voice from the control booth—when he’s been fired and replaced by Bob Johnston—Albert Grossman has been harrying him over the phone throughout, Wilson trying to fend him off, feeling the ax coming down—talking about how everyone detests him, he came from jazz, produced Coltrane and Sun Ra, thought folk music was worthless music played by worthless people, until he met Dylan. As with Bloomfield, the casting is free: Wilson was in his mid-thirties in 1965, but this Wilson is in his fifties or early sixties, crusty, with a film noir demeanor, the record producer as Humphrey Bogart or Lemmy Caution.

Out of this mise-en-scène they begin to try to find the song. At one point when Tom Wilson is called to the phone Kooper leaves the control booth and camps behind the organ when Griffin is momentarily up from the stool, hoping it’s “like a piano.” Wilson sees him, tells him to get out, and Kooper gets up. Dylan says wait, asks Kooper his name, can he play organ. Wilson says no, Kooper says yes, Bloomfield says he thinks he’s a guitar player (“Also,” says Kooper), and Dylan gives him a test: “Birth date of Woody Guthrie.” If he can answer that he’s in, if not, he’s out. “What?” Kooper says. Bloomfield whispers to him: “July 14, 1912.” Kooper repeats it. Everyone laughs, nobody is fooled, but he’s installed behind the organ anyway.

This will have echoes. Pouderoux has seemed too mannered in his Dylan impersonation (since we don’t know the others as people, there is no impersonation, but Pouderoux doesn’t recreate a Dylan as the characters in I’m Not There1 do), both vocally and physically (he’s very tall, though that isn’t a problem). But the mannered element burns off when he reaches the choruses of “Like a Rolling Stone,” when fervor rises and he, Pouderoux as a singer, attacks the words, and these moments, whenever a take makes it to the chorus, are thrilling, and you wait for them. But late in the play he too sits in a chair in the corner off the front of the stage, where it began with Kooper, and recites, fast and with utter belief, sarcasm, and commitment, the seven-minute (though it seems at least ten) “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie,” and it’s staggering, like knives through skin over and over, with that cold, hard ending, where Brooklyn State Hospital becomes a church. It seems connected, too, to the moment where, when the set has momentarily cleared, Gregg picks up Dylan’s acoustic guitar and begins to sing and play “Blowin’ in the Wind.” It’s not like any other version: he brings all of his character’s misery to bear on the song, and it comes out hopeless, defeated, quietly changed in an undeniable way, or opened up in a way that will forever change the song, and you don’t want Dylan to reappear and tap him on the shoulder and stop it, as he does. And that echoes too—throughout there are bits that you want to go on, that seem to have so much more to say or play with, that are cut and the play keeps moving. It seems to be much longer than the 75 minutes it is, because there is so much in it.

There’s the wonderful scene when, with Dylan off stage, in the middle of an electrical blackout, with everyone talking with their cigarette lighters burning, Gregg says, “‘Napoleon in rags,’ who’s that?” and Kooper says, “Kennedy”—just like people did when the song came out, when as I recall the most appealing interpretations were Martin Luther King or Dylan himself (“‘The language that he used’—she didn’t like Dylan’s songs!). “Why rags?” Gregg says. “Vietnam,” Kooper says. “I don’t understand,” Gregg says. “I don’t understand that you don’t understand,” Kooper says, in one of the best lines in the play. “These are metaphors, this song is political, everything is political.” (As if they’ve heard the whole song, which they haven’t.) At one point there’s an offstage monologue from Tom Wilson about how the key line is “You’ve got no secrets to conceal,” that the song is about freeing yourself of burdens, obligations, masks, rules, lack of confidence, lack of a sense of self, and achieving liberation—the song is a manifesto of freedom, and how hard it is to achieve it.

The session breaks down, reforms. At one point Griffin, who’s always hangdog, quits, runs off, and Bloomfield, who gains in presence throughout, who has an expression of deep reserves of musical confidence and self-worth, seems to take forever to bring him back. Bloomfield blows up, Gregg seems ready to die, and Kooper looks dopey and clueless. They push into the song, with Dylan playing head to head with Bloomfield in the tiny breaks between verses. At one point Gregg loses it, drowning everyone out, all of his self-hatred coming out. Bloomfield strips off his shirt and tosses it into the bass drum, to muffle it—maybe a gesture of disdain, maybe to say there’s no problem we can’t solve here, and then Kooper takes off his shirt, and then Gregg himself, with Griffin leaving on his undershirt, all the shirts tossed into the drum. It’s a weird moment of distance and camaraderie.

I’m not conveying how funny the play is, how much people laugh. When no one can work with Griffin’s piano, Bloomfield says, “Take off your glasses.” “But I can’t see anything without my glasses,” Griffin says. But he takes them off. Everyone laughs. Bloomfield and Dylan crack up. “Is this a joke?” Griffin says. Then there’s the wonderful break where Griffin says, “Did you ever hear about the printer from Kentucky? He died, and after the funeral, after he was buried, his son goes into his workshop and finds a bottle marked ‘Do Not Open.’ Everyone looks at it, but they leave it as it is. Every year on the anniversary of the father’s death they bring it out. This goes on for 20 years—and one day the bottle cracks. And what do you think was in it? (Everybody makes a desultory guess.) A bunch of labels that read ‘Do Not Open.’ So that’s what ‘Napoleon in rags’ means. Napoleon. In. Rags.”

Which doesn’t stop Gregg from later going on a rant about Edie Sedgwick and how Napoleon in rags is really Andy Warhol.

Time slips. Bloomfield says, “You know what Bruce Springsteen said about the first time he heard this song?” We’ll hear, from one character or another, about the future careers of the musicians, and Bloomfield’s death from an overdose—which given the person we’re looking at, Varupenne having nothing of Bloomfield’s Jewish nervousness, seems impossible to believe. At one point all the musicians dart into the aisles and turn into reporters asking Dylan typical 1965 press conference questions that he answers blankly, under his breath. “Do you prefer to make your message subtle or obvious? I heard it’s subtle.” “Where did you hear that? “I read it in, ah, a movie review.”

It’s this sort of reversal of perspective—as with the blackout, the stage-lip addresses, the shirts coming off (the result of a joke during a rehearsal that stayed in)—that keeps the play visually alive, never static, never flat or predictable, so that every moment is visually full as it is in terms of sound. And with sound, what the directors and the actors do with the many false takes of the song they play—too fast, too slow, the early stages of “La Baaamba” as a waltz—also keeps what could have been as dull as most recording sessions full of surprise and suspense.

Finally, they set to once more, and the play seems like it must be near the end, and the performance immediately has a confidence, a drive, that says this will be it. The actors/musicians communicate a a tremendous sense of action, of event. Pouderoux shakes his head at Varupenne with joy during the breaks and barely makes it back to the mike for the next verse. It’s carefully staged—as the previous take had still been “You used to make fun about,” now it’s “You used to laugh about.” For the first time, the fundamental, seemingly irreducible excitement of the song is present, and growing, and the audience is caught up in the sense of the event of the song itself. The actors have to make this seem like not a performance in a play, but a discovery they are making, and they do. Finally it’s over.

They call to the booth—and Wilson is gone. “Bob” answers. Bob Johnston. They listen to a playback on headphones, all standing at the front of the stage in a line. In silence, until Kooper speaks: “Yesterday I was lying in my bed and I said to myself, Al, you’re 71, take a look at what you’ve accomplished . . .” They each speak in a reverie. Bloomfield: “The end.” Kooper: “I was always an eighth behind.” Dylan: “You can play the organ?” Griffin: “But he doesn’t know how to play the organ.” Gregg: “Edie . . .” Kooper: “I knew how to accent it when the chorus came.” Gregg: “I made the sound that set it off.” Bloomfield: “That little climb in the song isn’t bad—”

—and at that moment, under their breath, they all mouth the final chorus. It’s almost mystical, otherwordly (like the background chant in the Gaslight version of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”), following, or riding, the song into the future, into the present, where four of them, Wilson (1978), Bloomfield (1981), Griffin (2000), and Gregg (2014), will be dead.

Noir

There are six curtain calls.

Notes

| ↑1 | I’m Not There, film de Todd Haynes, 2007, biopic experimental, où six acteurs interprètent six aspects de la vie de Bob Dylan. |

|---|